When David Price was chosen by the Tampa Bay Rays with the first overall pick of the 2007 amateur draft, it probably would not have surprised fans to find him as one of the best pitchers in the American League in the 2010 season. In between, however, has been an interesting journey with a number of adjustments for Price along the way.

Price made a rapid ascent through the minor leagues in 2008, dominating High-A Vero Beach and Double-A Montgomery with sub-2.00 ERAs, 92 strikeouts in 91.2 innings, and a sparkling 11-0 win-loss record. He was promoted to Triple-A Durham in August 2008 and held his own with a 4.50 ERA and 17 strikeouts in 18 innings. He was called up to the big leagues and debuted with the Rays in a pennant race, pitching mostly out of the bullpen in September. He pitched in three games in the American League Championship Series and two games in the World Series, striking out eight in 5.2 innings and acquitting himself well against October competition.

2009, however, was a year of struggles for Price. He was sent back to the minors to begin the season, and after he was called up in late May, he posted a 5.60 ERA through his first 11 starts, failing to finish the fifth inning in five of those games. Though he had posted 54 strikeouts in 53 innings, he had also given up 33 walks and 11 home runs. He finished the remainder of the season on a stronger note, recording a 3.58 ERA over his final 12 starts, allowing only 6 home runs and 21 walks in 75.1 innings, but also cutting his strikeouts to 48 over that time frame.

In 2010, David Price emerged as the dominant starter people expected when he was drafted. He finished third in the American League with a 2.72 ERA and boasted a splendid 19-6 win-loss record. His peripherals were solid, with 188 strikeouts in 208.2 innings against 170 hits, 79 walks, and 15 home runs allowed.

Let’s take a look at the pitches that Price throws and how his repertoire has evolved during his tenure with the Rays.

Evolution of his repertoire

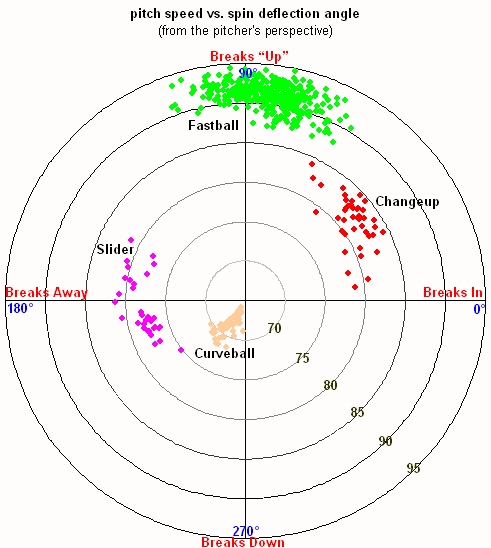

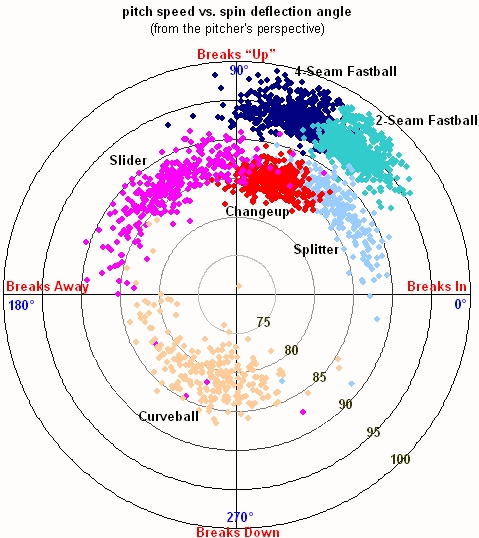

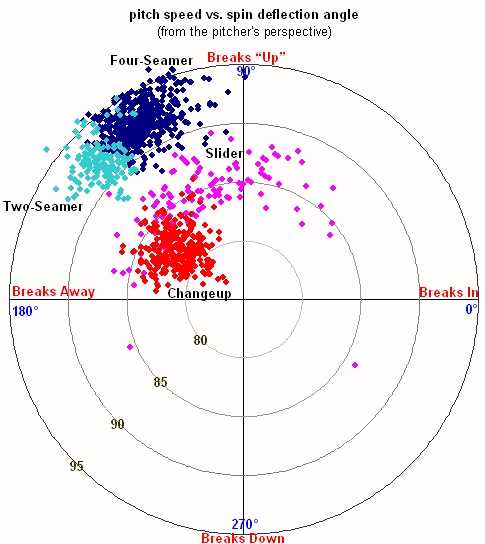

As you will see, classifying Price’s pitches can be a bit of a challenge when he’s frequently changing what pitches are in his repertoire. However, I’ll go out on a limb and say that Price has used six pitch types in the major leagues: a four-seam fastball, slider, curveball, and three variations on a sinking pitch which I have identified as a two-seam fastball, split-finger fastball, and changeup.

I’ll explain the varieties of sinkers and changeups in a moment, as well as his journey from one pitch type to another. Let’s start by talking about what Price threw when he broke into the majors in 2008, mostly pitching out of the bullpen.

For those of you not familiar with my previous writing, I enjoy analyzing the detailed pitch data that has been collected on pitchers for the past few years using the PITCHf/x camera systems that are installed in all 30 major league stadiums. PITCHf/x tracks the speed and trajectory of nearly every pitch thrown in major league games, and the information is available for download from Major League Baseball’s Gameday website. I have created a database of this pitch information and use it to analyze pitchers. A number of other analysts have done similar work, including Josh Kalk, who published at the Hardball Times before being hired by the Rays in 2009.

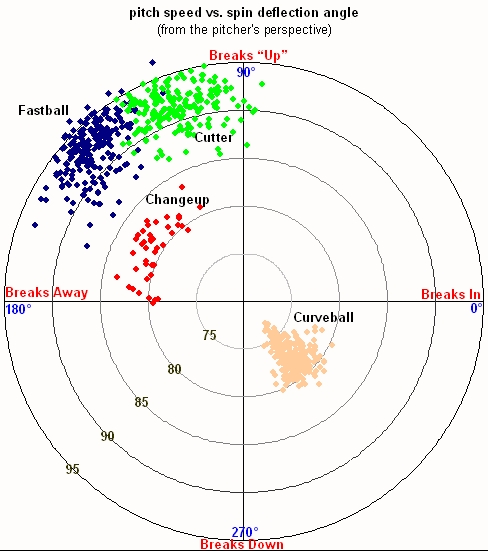

Let’s look at what the PITCHf/x data show us about the pitch speed and spin movement of the pitches he has thrown. We’ll go through each of the stages of the evolution of Price’s pitch repertoire, beginning with 2008.

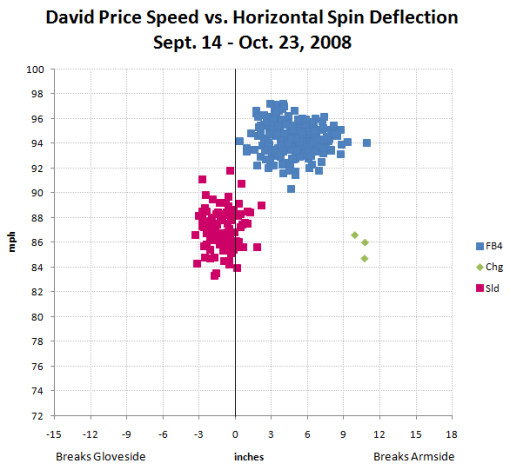

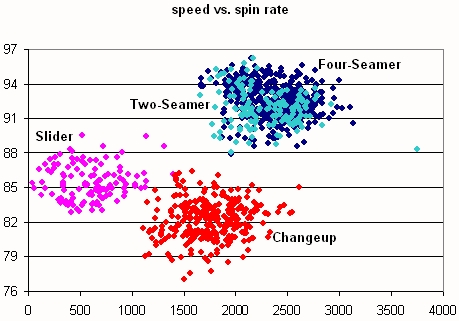

David Price was basically a two-pitch pitcher as a reliever in 2008. He threw a 94-mph four-seam fastball two thirds of the time, and the other third of the time he threw an 87-mph slider. He also showed a changeup, but it was not a regular part of his repertoire out of the bullpen.

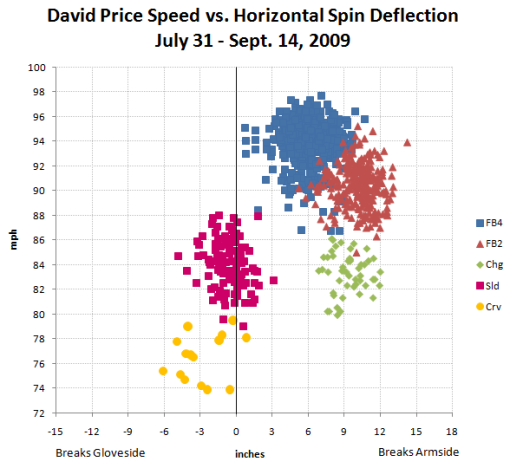

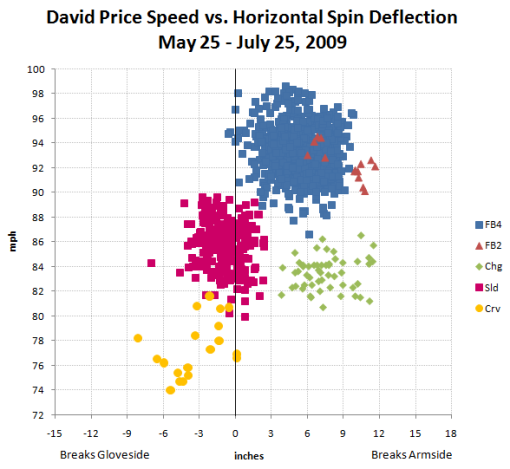

When he returned to the majors in May 2009 as a starting pitcher, he threw his four-seam fastball slightly slower, averaging 93.4 mph, but it was still his main pitch. He expanded his off-speed offerings to right-handed hitters, adding an occasional changeup and a rare curveball or two-seam fastball. You’ll recall that he was not especially effective during this period, and he struggled with his control.

In the second half of 2009, Price added a 90-91 mph two-seam fastball and cut back on his slider usage. He threw the two-seam fastball almost exclusively to right-handed hitters, and used it almost as often to them as he did the four-seam fastball.

In the second half of 2009, Price added a 90-91 mph two-seam fastball and cut back on his slider usage. He threw the two-seam fastball almost exclusively to right-handed hitters, and used it almost as often to them as he did the four-seam fastball.

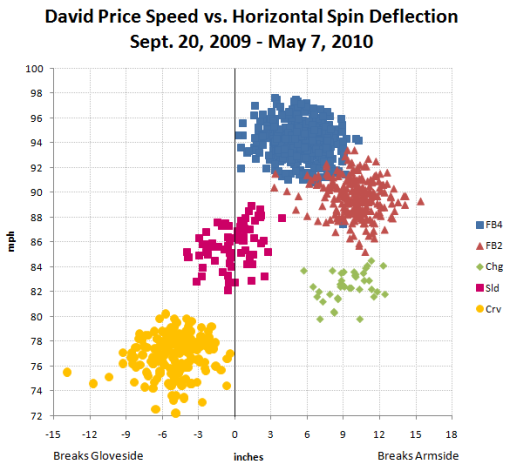

In his last three starts of 2009 and continuing into 2010, Price began to feature his curveball much more prominently and nearly abandoned his slider. He also increased the speed differential between his four-seam fastball and two-seam fastball, as he threw the sinking fastball only 89-90 mph.

In his last three starts of 2009 and continuing into 2010, Price began to feature his curveball much more prominently and nearly abandoned his slider. He also increased the speed differential between his four-seam fastball and two-seam fastball, as he threw the sinking fastball only 89-90 mph.

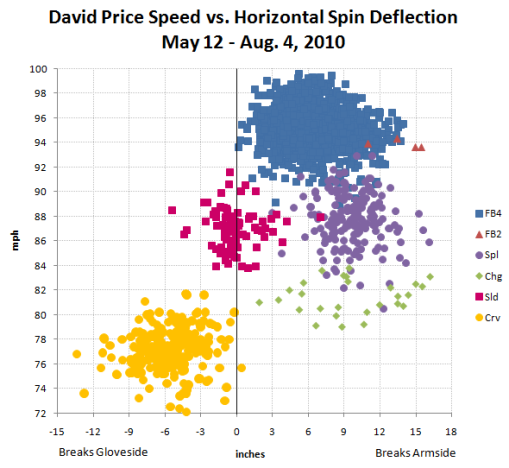

From May through August of 2010, the evolution of Price’s two-seam fastball continued. He decreased the speed of the pitch even further to an average of 87 mph, such that it could probably best be described as a split-finger fastball. At the same time, he upped his average four-seam fastball speed to 95 mph.

From May through August of 2010, the evolution of Price’s two-seam fastball continued. He decreased the speed of the pitch even further to an average of 87 mph, such that it could probably best be described as a split-finger fastball. At the same time, he upped his average four-seam fastball speed to 95 mph.

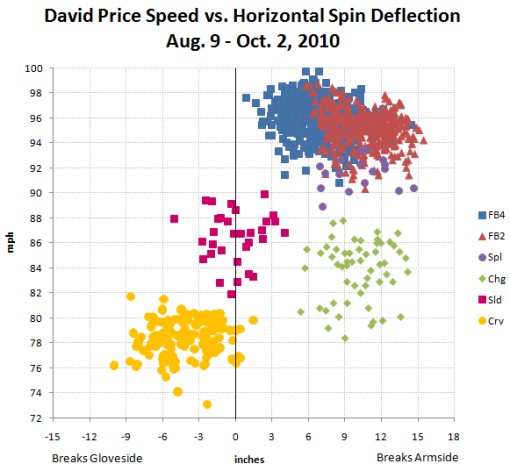

Finally, in August and September, Price largely abandoned the splitter (or whatever you want to call the high-80s sinking pitch) and replaced it with a harder two-seam fastball, thrown nearly as hard as his now 96-mph four-seam fastball.

Finally, in August and September, Price largely abandoned the splitter (or whatever you want to call the high-80s sinking pitch) and replaced it with a harder two-seam fastball, thrown nearly as hard as his now 96-mph four-seam fastball.

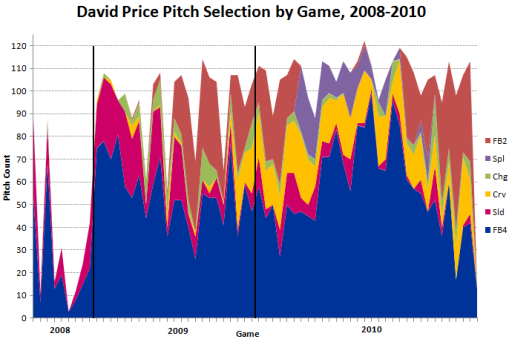

We’ve examined each of the major phases of David Price’s pitch repertoire development. Let’s view the same thing a different way by looking at his pitch selection by game throughout his career.

We see that Price began his career as a four-seam fastball and slider pitcher, then added a two-seam fastball, then a curveball. Next, he replaced the two-seam fastball with a splitter, then went back to the two-seam fastball. Toward the end of 2010, he increasingly favored the two-seam fastball over the four-seam fastball.

Pitch repertoire description

Let’s talk a little more about each of his pitch types.

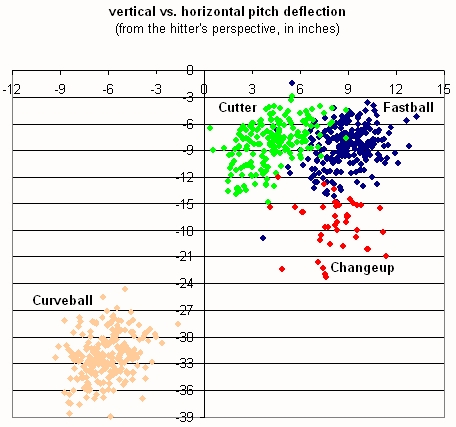

First, the four-seam fastball. Price has gained speed on his four-seamer in 2010. In 2008, mostly in relief, his heat was measured at an average of 94.3 mph by PITCHf/x. In 2009, it was measured at 93.5 mph; however, the Tampa Bay PITCHf/x system was recording speeds about 0.8 mph too slow that year. That would imply Price’s real 2009 average fastball was more like 93.9 mph, assuming a roughly equal number of pitches at home and on the road. In 2010, his average four-seamer was recorded at 95.2 mph. The Tampa Bay PITCHf/x system was still recording speeds about 0.8 mph too slow until mid June; after that it was fairly well calibrated for speed. The calibration adjustments to the PITCHf/x data give us an average four-seam fastball speed of about 95.4 mph for the 2010 season, or 1.5 mph faster than it was in 2009.

There has been some talk about Price progressively increasing his fastball speed during the 2010 season. I believe this perception was mostly, but not totally, an artifact of the PITCHf/x calibration adjustment in mid June. In August and September of 2010, his four-seam fastball averaged about 95.9 mph.

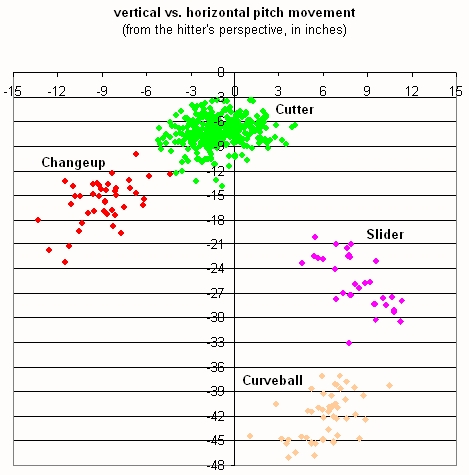

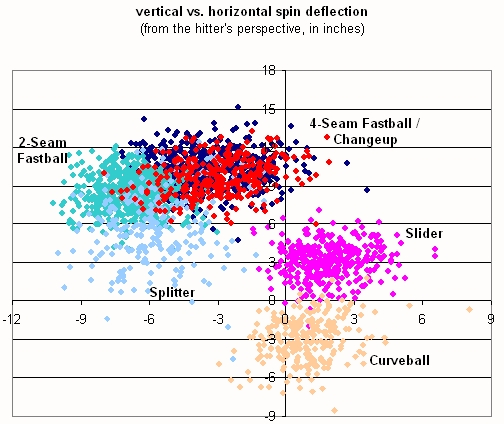

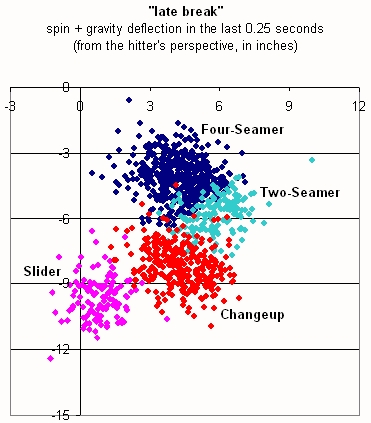

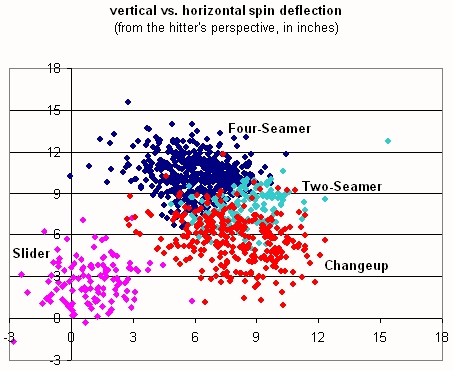

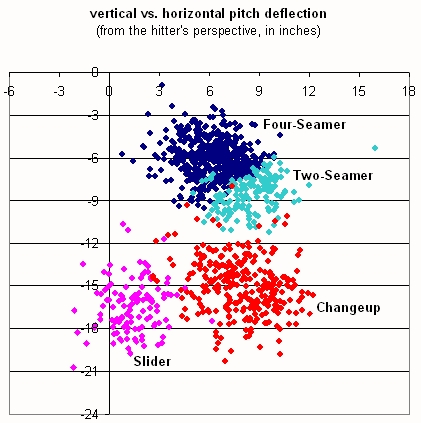

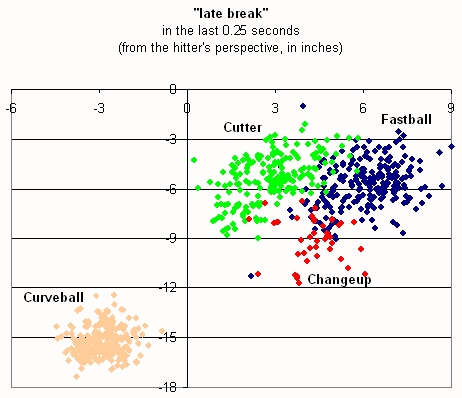

Price gets about eight inches of hop and seven inches of tail on his four-seam fastball. That’s pretty typical for a major-league four-seamer. He heavily relies on the pitch to left-handed batters, throwing it 75 percent of the time to them during 2010, whereas to righties he throws it only 49 percent of the time and mixes in the two-seam fastball. The four-seamer is his primary strikeout pitch, generating 85 percent of his strikeouts of lefty batters in 2010 and 67 percent of his strikeouts of righties. Price uses a classic four-seam grip, which you can see here.

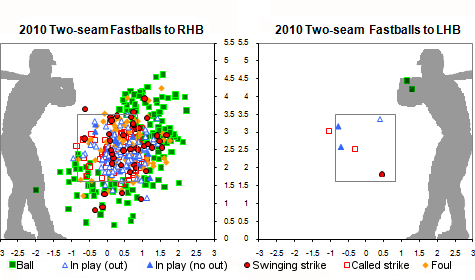

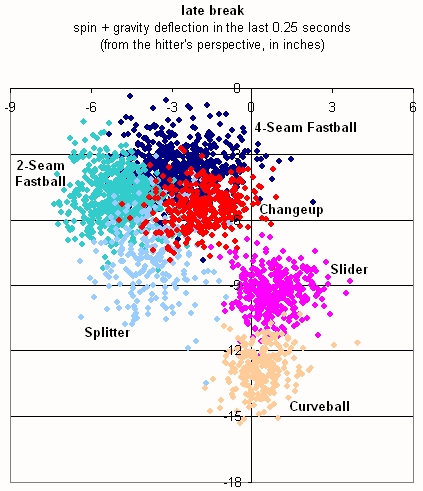

We discussed earlier that David Price debuted a two-seam fastball in the second half of the 2009 season. To recap, it was a pitch he threw 90-91 mph, about three mph slower than his four-seamer. In 2010, he switched to a slower version that I’ve called a split-finger fastball before returning to a much harder two-seam fastball in August and September. This new two-seam fastball averaged 95.1 mph, or within one mph of his four-seam fastball. He gets about six inches of hop and 11 inches of tail on his two-seam fastball, which is about four or five inches of movement relative to his four-seamer. In August and September, Price used the two-seamer only six percent of the time to left-handed batters but 37 percent of the time to right-handed batters. You can see his two-seam fastball grip here and here.

Price’s split-finger fastball, as I’m calling it here, is a slower version of his two-seam fastball that existed primarily from May 12 to August 4, 2010. His average speed on this pitch was about 87.4 mph, or almost eight mph slower than his four-seam fastball. That’s almost a changeup speed differential, and I might have called it a changeup were it not for an even slower offspeed pitch type thrown by Price, which we will discuss in a moment. His splitter gets about five inches of hop and nine inches of tail, fairly similar to his two-seamer. During the time period where this was his main sinking offspeed pitch, May to July, he threw it 15 percent of the time to right-handed batters and rarely, if ever, to lefties. (I counted two such instances.) I’ve looked for game photos of his splitter grip from games in the May 12 to August 4 time frame, but so far I’ve had no luck finding any. I’d guess his splitter grip is pretty similar to his two-seamer grip, with the variation coming in how tightly he grips the ball into his palm rather than from major changes in seam orientation.

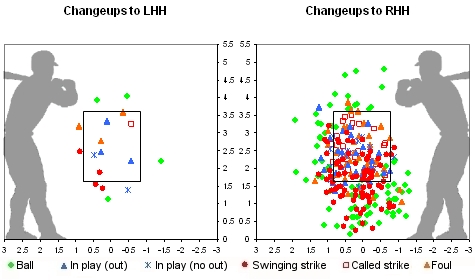

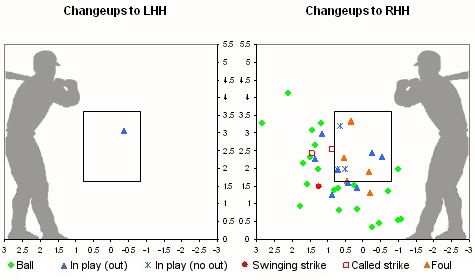

As mentioned previously, Price has another slower sinking off-speed pitch. I’ve called this pitch type a changeup. His changeup averages about 83 mph, or 12 mph slower than his four-seam fastball. He gets about seven inches of hop and 10 inches of tail on his changeup, very similar spin movement to his two-seam fastball. He has thrown the pitch exclusively to right-handed opponents, about four percent of the time during the 2010 season. I’ve not been able to find a game photo that I can conclusively identify as a changeup grip, but this one looks suspiciously like a circle change to me, though it wasn’t taken from the best angle for grip identification.

Coming up through the minors, Price’s slider drew high praise, and it was his main secondary pitch at the end of the 2008 season. However, we’ve seen a lot less of the slider since he developed the curveball toward the end of 2009. He throws the slider about 86-87 mph, with very little spin movement. When it was his main breaking ball in 2008-2009, he threw it equally to righthanders and lefthanders. In 2010, he used it mostly to lefties (12 percent of the time) and rarely to righties (three percent of the time), preferring instead to use the curveball against right-handed batters. You can see a photo of his slider grip here.

There is some indication in his last couple starts, September 23 and September 28, 2010, that Price might be evolving his now seldom-used slider into a cutter. The slider was thrown a little harder with a little more hop in those two games. It’s a very small sample size, a total of five pitches, but it was enough to pique my curiosity, and it’s something I’ll be paying attention to in the playoffs.

Price’s favorite breaking pitch is now a curveball. He throws the curveball at about 78 mph on average, and he gets five inches of cut and eight inches of drop due to spin. If you include the effect of gravity, his curveball drops about 2.5-3 feet. In 2010, he used the curve 11 percent of the time to left-handed batters and 17 percent of the time to right-handed batters. He uses a spike curveball grip that you can see here.

Pitch mix

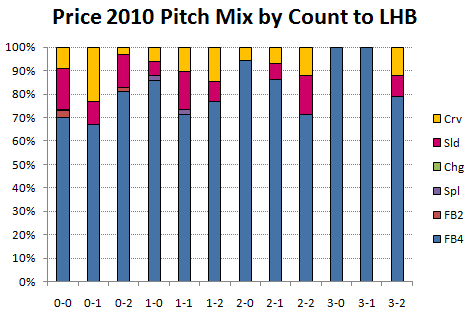

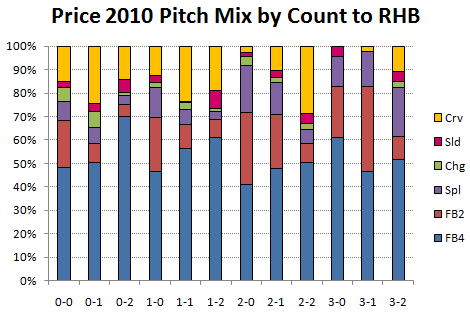

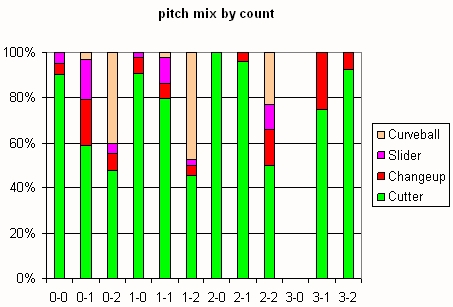

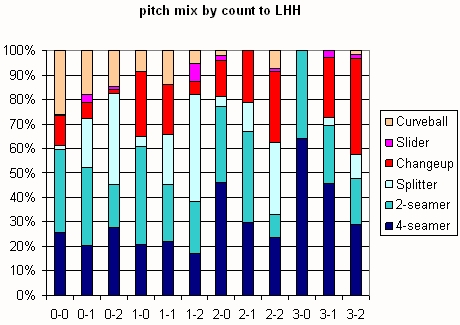

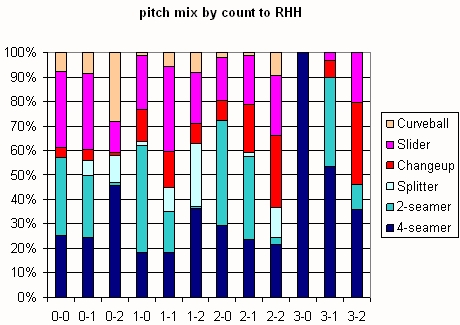

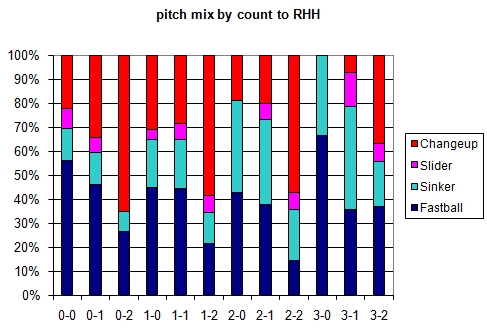

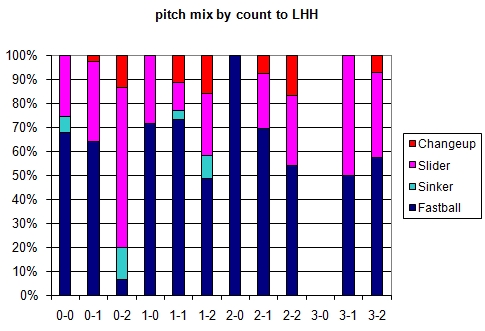

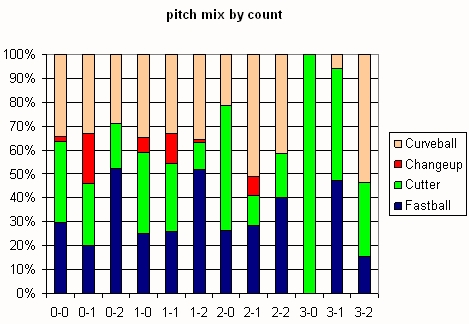

We’ve looked at some changes in Price’s pitch repertoire and examined some of how he uses each of his pitches. Let’s also look at how he mixes his pitch types in different ball-strike counts. Below, I show his pitch mix for 2010, split out by batter handedness.

To left-handed batters, Price uses mostly his four-seam fastball. This is especially true when he falls behind in the count; lefties will see the four-seamer 87% of the time in this case. When he is even or ahead in the count, he’s a little more likely to throw a breaking pitch (26% of the time).

Price uses his off-speed and sinking pitches more freely with right-handed opponents, though he still favors his four-seam fastball as a strikeout pitch on 0-2 (70% of the time). He throws his curveball most often (19% of the time) to righties when even or ahead in the count, and his splitter and two-seam fastball when he gets behind in the count.

Pitch results

What kind of results did Price get with each of his pitch types in 2010?

| Pitch | Number | Ball | CS | Foul | SS | InPlay | BACON | BABIP | SLG | HR | Strk% | Con% |

| FB4 | 1841 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.319 | 0.299 | 0.500 | 0.028 | 66% | 77% |

| FB2 | 507 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.219 | 0.205 | 0.325 | 0.018 | 67% | 82% |

| Spl | 208 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.327 | 0.300 | 0.481 | 0.038 | 66% | 81% |

| Chg | 105 | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.208 | 0.208 | 0.292 | 0.000 | 67% | 86% |

| Sld | 172 | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.135 | 0.086 | 0.361 | 0.054 | 65% | 79% |

| Crv | 521 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.342 | 0.333 | 0.468 | 0.013 | 61% | 81% |

Price has thrown all six of his pitch types for strikes this year. The four-seam fastball and two-seam fastball generated impressive whiff rates, 11% and 9% respectively, as compared to 7% and 6% major-league average. His off-speed and breaking stuff, however, was not terribly impressive in that regard. He had some pretty low batting averages allowed on balls in play (BABIP) for the two-seam fastball, the changeup, and the slider. I looked a little deeper into this but did not find any patterns that suggested this was likely to be a persistent trend. It’s possible I missed something that data from additional seasons may reveal more clearly.

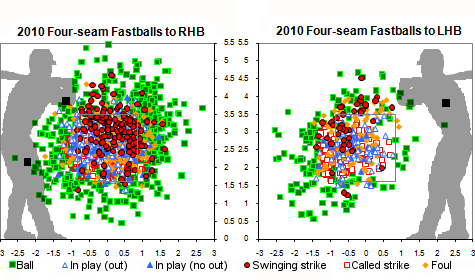

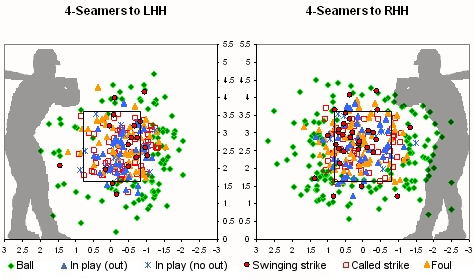

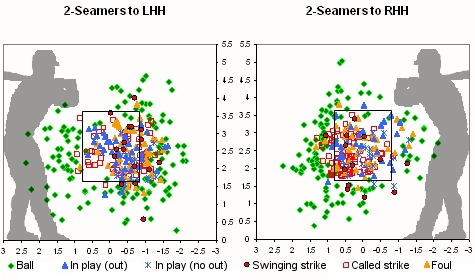

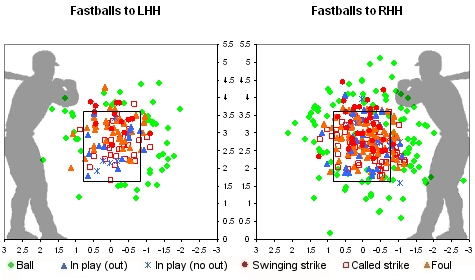

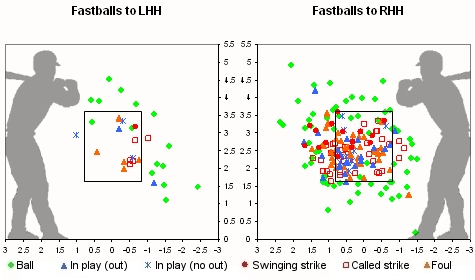

Let’s look now at where he locates his pitches to right-handed and left-handed batters. Strike-zone location charts are shown from the perspective of the catcher. The location of a pitch is indicated where it crossed the front plane of home plate.

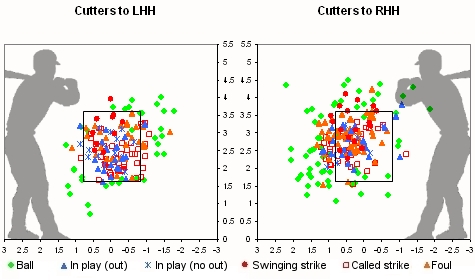

The first thing that is obvious from this graph is that David Price faces many more right-handed batters than left-handed batters. Price has faced 77 percent right-handed batters; this is fairly typical for a left-handed starting pitcher. Against righthanders, Price throws his four-seamer both inside and outside. He’s very successful at getting swinging strikes when he gets the ball up and away within the strike zone. Against lefthanders, he keeps the four-seamer away, and he gets quite a few called strikes where the umpires typically expand the outside edge of the zone to lefty batters.

The first thing that is obvious from this graph is that David Price faces many more right-handed batters than left-handed batters. Price has faced 77 percent right-handed batters; this is fairly typical for a left-handed starting pitcher. Against righthanders, Price throws his four-seamer both inside and outside. He’s very successful at getting swinging strikes when he gets the ball up and away within the strike zone. Against lefthanders, he keeps the four-seamer away, and he gets quite a few called strikes where the umpires typically expand the outside edge of the zone to lefty batters.

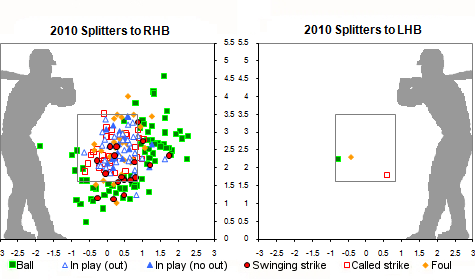

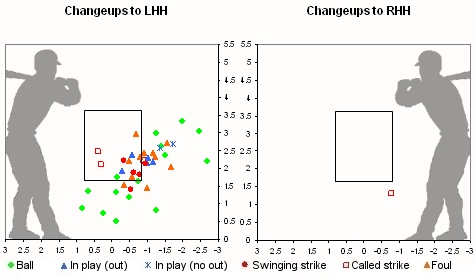

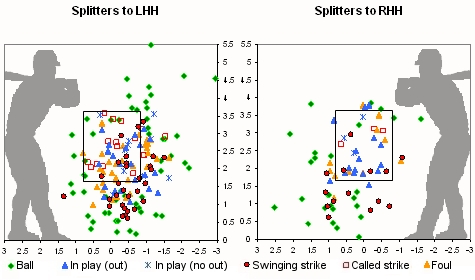

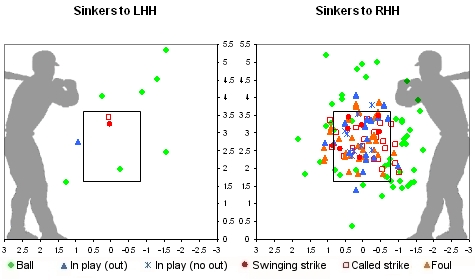

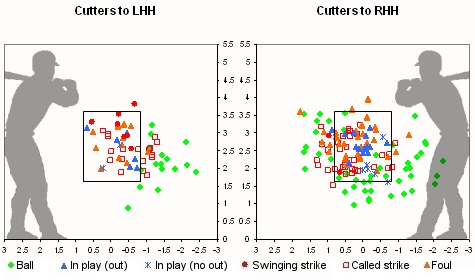

Price pitched with a similar pattern with all of his sinking pitches: the two-seam fastball, the split-finger fastball, and the changeup (as I have labeled them), so I’ll discuss them together. He rarely throws any of the them to left-handed opponents. To right-handed batters, he kept them on the outside edge. He does well at throwing them for strikes, and the two-seamer seems to be the best of the three at fooling opponents into swinging and missing.

Price pitched with a similar pattern with all of his sinking pitches: the two-seam fastball, the split-finger fastball, and the changeup (as I have labeled them), so I’ll discuss them together. He rarely throws any of the them to left-handed opponents. To right-handed batters, he kept them on the outside edge. He does well at throwing them for strikes, and the two-seamer seems to be the best of the three at fooling opponents into swinging and missing.

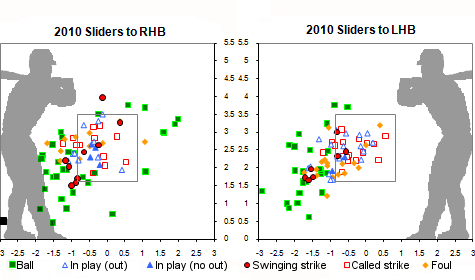

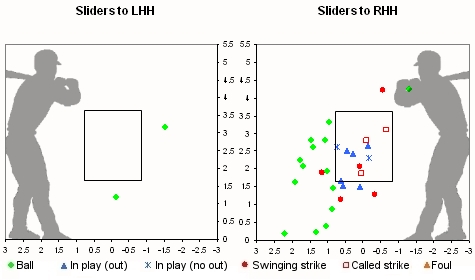

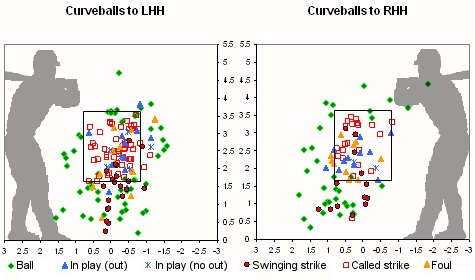

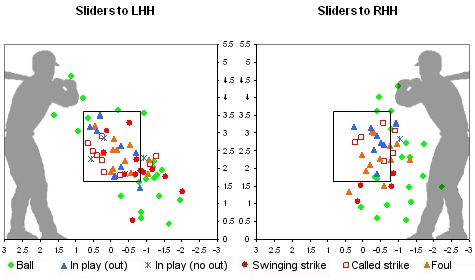

As already discussed, Price cut back on his slider usage in 2010. When he did use it, he kept it away from lefties and brought it inside to righties, which is a typical approach for a left-handed pitcher. Price was able to throw the slider for strikes, but otherwise it was fairly unremarkable, generating below-average numbers of whiffs.

As already discussed, Price cut back on his slider usage in 2010. When he did use it, he kept it away from lefties and brought it inside to righties, which is a typical approach for a left-handed pitcher. Price was able to throw the slider for strikes, but otherwise it was fairly unremarkable, generating below-average numbers of whiffs.

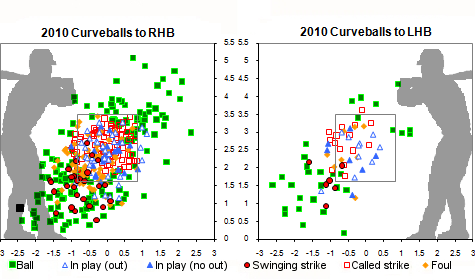

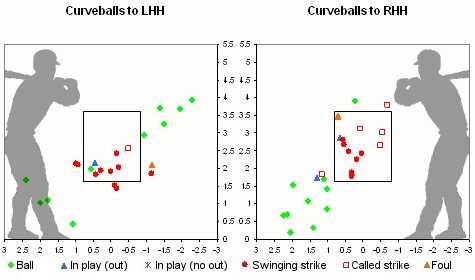

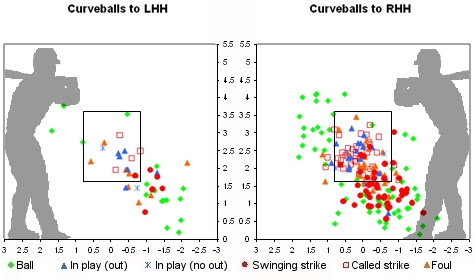

On the other hand, Price used the curveball much more like a typical breaking pitch, inducing swings and misses on pitches down and out of the zone, though again, his whiff rate on the curve was below average when compared to the league. To right-handed batters, he mostly kept the curveball across the middle of the plate, and he was able to keep it in zone at a slightly above average rate (62 percent vs. league average of 57 percent). Against left-handed batters, he moved the curveball more toward the outside edge, and consequently, his curveball strike rate was lower to lefties (57 percent).

On the other hand, Price used the curveball much more like a typical breaking pitch, inducing swings and misses on pitches down and out of the zone, though again, his whiff rate on the curve was below average when compared to the league. To right-handed batters, he mostly kept the curveball across the middle of the plate, and he was able to keep it in zone at a slightly above average rate (62 percent vs. league average of 57 percent). Against left-handed batters, he moved the curveball more toward the outside edge, and consequently, his curveball strike rate was lower to lefties (57 percent).

Conclusions

It has been interesting to watch David Price develop into the ace of the Rays’ pitching staff. It has been fascinating for me to dive into how he accomplished that and to learn about the evolution of his repertoire across seasons. It’s rare that a pitcher is that willing to continuously experiment, adapt, and evolve.

He has a dominant 95-96 mph four-seam fastball that serves him well against left-handed batters and a four-seamer/two-seamer pairing that has helped him improve against right-handers in 2010. His breaking pitches are average offerings that fill out a solid repertoire. Though his performance on batted balls going forward may not be expected to be as good as it was in 2010, his stuff certainly seems to support his ability to carry the mantle of staff ace in the future.

Fast Balls RSS

Fast Balls RSS

You must be logged in to post a comment.